.

Reposting this as it showed up as one big illegible paragraph to some readers, sorry. I don’t really feel like it, actually, I just feel so sad about what my country is doing to immigrants. But I think we all need to learn how to say no. Hence, this.

This essay was published in Wag’s Revue, edited by Sandy Ernest Allen, and later named “notable,” in the 2014 Best American Essays by John Jeremiah Sullivan. Wag’s Revue has since closed. A decade +1 ago seems like much longer, no?

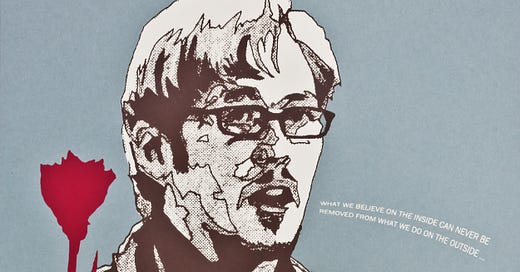

The image below if of a poster by Aaron Hughes, for IVAW and Just Seeds.

¡Joshua Casteel, PRESENTE!

.

DEAR JOSHUA

by Mary Margaret Alvarado

Joshua Casteel (December 27, 1979-August 25, 2012), was a veteran of the Long Wars, a writer, teacher, activist, and my dear friend. As an Army interrogator with the 202nd Military Intelligence Battalion, Joshua worked at Abu Ghraib Prison, where he underwent a crisis of faith, and became a pacifist. After applying for conscientious objector status, Joshua was assigned to the “burn pits.”

.

.

22 September 2012

Dear Joshua,

This morning on the porch, I found two kohlrabi and a cucumber. Who left them there and why? This is the mystery, or one of them. I chopped the cucumber and stirred in some peanut oil, the last of the rice vinegar, and salt. Then I added sweet corn, green onions, and basil. Kohlrabi are supposed to be treated like turnips; that’s all anyone has on the kohlrabi front. So maybe I’ll mash them? Or roast them? Or put them in a soup?

If this were a conversation, we wouldn’t have made it past salt. I know that. We’d be knee-deep in ontology by now, with you in the absolute lead. But it’s just me, and we haven’t talked in a while, and I owe you a letter.

Bess cried around three, ready to nurse. It’s funny how she can do this without waking. I asked Nico if he could imagine just, say, falling asleep halfway through eating a burrito. He got almost misty-eyed at the prospect and said, yes. He could imagine that, yes. So I woke, and nursed, then I returned to my dream of islands that I arrived at under duress. Around six, Lucy crawled into bed with us. Then she wrapped a slap bracelet around her calf like she was getting dressed for work, got out her bag of mail, and began to color all over each letter and card. Who was she writing to? I asked. “People who died, the sicks.” I said I’d write to them too.

When I came out of the study, looking for more coffee, they were all in their pajamas, dancing around to Perry Como’s “Magic Moments.” I joined in on “Papa Loves Mambo.” Then on to that Mirah song that goes, “Meet me at the back shack, baby / You’ll bring your little ukelele.” Bess was in the crook of her papa’s arm, gnawing on a wooden donut. Lucy shook her tiny hips.

Today is a nice day, a Saturday. Things are crisp in the loveliest and least melancholy way. I walked to the little store. We walked downtown. One of the two guys who live in their cars where our street meets the park was holding court from his opened van doors. He stopped me to ask what I thought about “the new improvements”—the mosaics plastered on light poles. “I love them,” I said. I want to ask you if you do too.

We went to an experiment that you would have liked. Take a block, and for twenty-four hours, make it different. Here, it was this: parked cars off the street, traffic down to one lane, bikes everywhere, a row of food carts and rickshaws, jigsaw puzzles on pretty blankets over oil stains in the converted parking spaces, trees in horse troughs making shade, sweet potato vines spilling, and low strings of winking solar lights. The idea is that if you show people that the world can be different, then they’re more likely to work for a different world. That was something you did, Joshua.

I remember the first time I heard you talk. We’d driven from Iowa to Indiana—a drive we would make many times. You spoke of soldiers unburdening their hearts to you in the bathroom at Abu Ghraib. You said all the mechanisms of torture hadn’t been eradicated; they’d been moved. You talked about not being able to pray many prayers as the dissonance between those words and your life was too great. You said, “Aslan isn’t safe, he’s good.” You said you were trying not to suck, which was funny then, and is funny now, because what we thought (Liz and I) was: THERE IS NO WAY TO TELL PEOPLE THEY ARE WALKING AROUND SHINING LIKE THE SUN. Because you were. You were so bullshit-free, we had to avert our eyes. You showed us how an interrogator could listen to a prisoner; how a soldier could put down his weapon; how a Christian could best hear these words from a Muslim: Turn the other cheek. Love your enemy. And then do that. You did that.

You showed us how a young son could put his work aside and move home and care for his dying father—lifting and bathing and feeding him. Then when you got sick, from the same disease, just one year later, you said “Why not me?” which messed with our heads. You found goodness where we strained to see any. You said your suffering was like the suffering of the Iraqi people, and that there was even “a certain sense of relief” that you shared this with them. You said we’d burned those toxins in their fields, poisoning their children and their food. You wed your suffering to theirs and set about reconciling all of us. Not what are we supposed to do with that?

You died 28 days ago, Joshua. I’ve been doing awesome flips in my head to avoid this plain fact. Even after your funeral, with your face on the program, I still don’t believe it.

I got the news like a lot of people. It came through my computer. I read, “Our hearts are broken,” on the CaringBridge website, then I got down on the floor and sobbed. I imagine your many friends in many places did the same. Later I tied Bess to my body and we walked out into an obscenely lovely afternoon. I had on sunglasses so no one could see my crying. Bess held my pointer fingers in the warm knots of her hands and tethered me to earth like she does. That evening I did the only thing that seemed right—I sang every verse of that Easter song you liked, trying to overcome the crying with a stronger thing: the singing.

You know what the world seemed like the next morning and the morning after that? It seemed shabby. It seemed inexcusably shabby. I felt so tired. All the colors had seeped out and gone somewhere. I think I thought: What the fuck? How can he die. He can’t die. He’s young and tall and strong and he has all those projects planned! Remember our magazine? Your film company? The Jesuits? That was some of my very American logic: a to-do list keeps you alive. Oh, but it was more, too. I thought (I keep thinking): Joshua has more energy than all of us! Clearer vision! Greater faith! Because you did. You do.

The day before your funeral Shawn asked if you and I had ever dated and I laughed. I remember the first time we met, over lunch at Hamburg Inn No. 2. We both knew a woman who was a human shield in Gaza, and she said we should be friends. I think I thought we’d flirt. I thought we’d flirt, or practice our special irony and knowing wit, or circle around each other like spies, because those were things I trucked in then. But there was no flirting, no irony, no armor. You were disarmed. And you disarmed the people you met. I was eating a veggie burger with too much mustard. You were talking about what we owe each other, which is nothing less than everything. I was working my way through slightly soggy fries, and you were like the man that Plato posits: the one who contemplates the Good. You were like Shadrach, Meschach and Abednego, joyfully defying the king, with the furnace heated seven times hotter than usual. You were like, Here I stand (in the Java House, in Prairie Lights). I can do no other.

After you died (in New York, on a Saturday), I found two letters I’d written that I had not sent. I found an email about a trip to the cabin that never happened, and an email about you coming to Colorado to give a talk that never happened. I found the beeswax candle I meant to send to your mom. I asked you to forgive me. I wondered if you could see me. I felt like I needed to be better than I am.

Then I tried to escape this fact—New York, at 3:30 on a Saturday, and only thirty-two years old—the finality and strangeness of it. We took the girls to a vast lawn full of misplaced ducks and I ran around barefoot, doing slightly manic figure eights, and Lucy followed suit, and this seemed like one of several ways to mock death, which is something I love about Halloween and generally want to do.

For several nights I painted the floors gray and listened to you. There are so many recordings of you talking, and I keep hearing new things, like this: how you have friends who have been tortured, and friends who have tortured (which is a paraphrase of history, in which we are all complicit), and you ached for all of them, for us. Your words are prophetic, an antidote to the age. But I was happiest just then to have these artifacts of how you said “umm.” I like how you said “umm.” I turned off the computer when you mentioned the jar of holy dirt from Chimayo that a friend sent to me for healing, and that I’d sent along to you, because I had no idea what to do with that or anything, and I couldn’t bear to hear your hope.

That night I made a list of everything I remember, wanting each hour to be distinct, even as they conflate into one long walk beside the Iowa River, and one long drive through the low frosted fields of the Midwest.

I remember the first time you showed me your writing. It was 80-some pages, single-spaced in 10-point type and the subject could be summarized as Heidegger + Everything.

I remember reading Andre Dubus aloud while crossing the Mississippi River. Your car was messy; your car was usually messy.

I remember drinking beer at an Irish pub with some South Bend pacifists and your mother, and how happy you were that night.

I remember you and Katie flirting and how her eyes got bluer, they actually did.

I remember meeting your parents in the frozen aisle of the Coralville Co-Op and being taken aback by their beauty.

I remember visiting the house they’d made out of an old church, and how your family delighted in each other, and how none of you had died.

I remember the places you lived, and how each was unlike the other: the ascetic studio over Gabe’s, where whatever band was playing and cigarette smoke rose through the vents like an update on chant and incense; the blue-porched Victorian you shared with the philosophy grad student in the neighborhood of official grownups; the suburban two-bedroom, with the security code keypad and wall-to-wall carpeting. In every home you opened the door the same wide way: you smiled, come in, there was something you were thinking about.

I remember eating watery soup with you and some old Mennonites in a farm town, and passing around actual mimeographs (they felt wet), and talking about nuclear disarmament and recipes.

I remember you describing the cross, and how nothing made sense to you without it, and how there should be a body on it, because there was and there are.

I remember how you dreaded the Fourth of July—idolatry of the nation state plus explosions. You said you’d be hiding in a basement, like lots of other vets.

I remember going to your play. We could see you shaking when you performed what you’d lived.

I remember talking on some long drive when my full-time love life was nothing if not exciting, but I wanted to be home, and I wanted to have children, and these states seemed impossible then. You said, very calmly, that you were sure that would happen, and I borrowed your peace for my own.

I remember eating fried waffles in a dim restaurant in the Quad Cities before you were confirmed. We sat across the table from Fr. Whatshisbucket and a woman not much older than us who had lost her teeth and couldn’t pay for more. You loved both of them. You took people seriously and you loved them.

I remember your straight and open posture. (When I imagine you, you are standing).

I remember those silly barefoot shoes.

I remember when you and Sam cheerfully moved my enormous metal desk and filing cabinet through all those narrow doorways and up and down too many stairs.

I remember when Griff picked up that guy he knew who’d been in recovery and was now passed out on the street, and we drove around South Bend with him, but it was Sunday or something, and the detox places were closed or overflowing, so Griff put him in a fat brown chair at the Catholic Worker house and drew the curtains to make it calm, and locked the door, and you and I stayed with him while he came to. I remember he said that he’d woken up “blowing numbers,” over and over with something like shock or shame. I remember that you spent most of that day on the couch near him, and kept kind silence or conversation until his shaking got steady and he groaned a little less.

I remember the month when Bess was on oxygen; you texted me all the time and more than any other friend. When you put your cannula in at night to breathe, you said, you were thinking of her, and how was her breathing? Your strong spine was crumbling and everything hurt. You had Stage IV cancer from a war you’d left in protest, and you kept checking in to see how our two-month-old baby was doing, how I was doing. You sent her a package with a pretty white dress. Then you prayed for her; you always prayed. Even as your lungs clouded, you prayed that hers would clear.

I remember the last time I saw you, two months before that. Liz and I were prepared for something somber, but you wanted none of it. You wanted to talk about the skiing competition that was on TV; and Jill (you missed her, you wondered about getting her back); and your syllabus; and Columbia College; and vegan recipes; and where to get the best organic produce; and various doctors; and the new translation of the Mass; and the lectures Griff had sent; and what commuting to Chicago might be like and whether to go by train; and my pregnancy; and the people in the photos on the wall. You wanted, in brief, to make your version of small talk. It was the only time I’ve known you to do so, and it made me glad; it seemed like a way of saying I want to be alive, which you did. You wanted to be alive.

At some point you and I were alone and you said a thing that made a bright and terrible blank in my brain—how it was part of your work to suffer, and it had been all along, and you understood this. And you said that you thought this cancer would kill you, but not yet. It would go away, and you would get to do the chief things you meant to do, and then, some years later, it would take you. I remember thinking, Okay? Okay! Let’s go with that—ten, or fifteen, or twenty more years. That sounds like a fairer deal.

But you didn’t get those years. You didn’t even get a year. And at the end, from what your mother said—and she’s become our teacher, she’s teaching all of us—it was not a passing, or a thin place, or a decrescendo, or a veil. It was excruciating and it choked you and you fought. It was the cup you wanted to pass. It was what she had mightily strived and prayed against. It was a cross.

I had planned to see you the first weekend of October. I did not. The head of Iraq Veterans Against the War said he had planned to see you the day you died. He did not.

Janani was the last friend I know at your side. And it seems significant to me that she was. She’s a culturally Hindu agnostic girl with recent Buddhist leanings who sometimes identifies as a boy. Here’s a common cup: she loved you—the straight, blonde, culturally evangelical Iowan who could quote scripture chapter and verse.

Two days before you died, she brought you bananas that you could not eat, one of which broke from its stem.

She wrote a long note, which was “raw,” she said, like she felt.

“I honestly don’t know how much he heard or understood. I read all the letters [sent from friends] and he just seemed to be sleeping. […] I talked to him for a while and gave him some hugs, and then he woke up—in a manner of speaking. His eyes opened and he appeared to focus on us for awhile. I kept talking—I don’t think he knew it was me.

‘Let them in,’ he said, in a very small voice. ‘Let them in.’

Then: ‘friend?’ (As in, ‘is it a friend?’)

Then he grabbed my hand really tight and his mom asked if he wanted me to go (I was about to leave) and he said no no no.

Even though I still don’t think he knew who I was.

I put my head down on his chest and cried all over his hospital gown. To get all the time back.”

To get all the time back.

She said the “shapes and shadows” of you were so clear, and all your “sharp bones.” She said, “What the hell? He looks so handsome.”

“If it weren’t cancer, if it weren’t fatal, if it weren’t illness, I would wish for everyone to dwell in this state—so rested, so vulnerable, so receptive, so yielding, and so ready to BE together. From nobody except a person in a hospital bed would I accept or even understand that kind of hand-squeeze: no no no don’t leave me.”

It crushes me to know these words you said. You said, “Let them in.” And, “Friend?” You said “friend.” And you said no no no, because you loved your own, and you loved them until the end.

In the weeks after your death, I began to build a narrative on a falsehood you would have rejected. It was bleak and pinched and went like this: goodness is finite, like a commodity. So when I boarded the plane to your funeral I saw what I was looking for: people all over America fondling their profile pictures. Even as I cooed at Bess, and spotted her on every chair, I braced myself for a living cliché: a self-important businessman who couldn’t possibly turn off his devices until the last possible moment; a man who would dominate both armrests and let me know that babies were distasteful, while I folded myself into a tiny package and tried to inoffensively nurse. (See how blameless I am in this fantasy? Impressive, right?)

But Bess and I were seated next to a kind woman and my narrative fell apart right then. And guess what? She was your high school girlfriend. She was like a lot of your people: lit straight through and very tender from the sorrow of losing you. Your high school girlfriend is a doctor who works with dying kids. We talked about The Spirit Catches You and You Fall Down, and cross-cultural medicine, and how you two dated, and her hopes to have a child, and another friend with cancer, and the quiet she tries to store up each week.

When we landed in Cedar Rapids it hit me that you were the last person to meet me there. And I looked for you. I keep looking for you. You would be the tall guy, smiling.

Shawn was there, though, and Liz. And they’d brought a carseat.

The air in Iowa was feathered, with the light filtered through a fine gauze. It is difficult, in such air, to not believe that the living are accompanied by the dead. And then there was the town: all those blocks broken up by empty lots where a footprint of a building stands but the concrete has succumbed to green green weeds, and you see the one thing, being born from the other.

We drove around and talked about you. We’ve been flocking towards you, like cold people go towards warmth. We all agreed that there was a great deal of mystery in the way that you died. That it wasn’t simply a government-sponsored murder, though you are, it’s clear, a victim of the wars.

That night, I put Bess to bed and Shawn and Liz went to find pizza. Bess lives like this: wherever you go is home, my mama. And milk is the smell of that home. We slept on sheets that are much fancier than ours, and she did an elaborate and charming waggle as she settled herself onto them, hoisting her bottom up, then smoothing her fat, starry hands across the silky expanse.

Liz and Shawn know how to do a wake, which should involve, at a minimum, some drinks and some stories. The word we got was that the best pizza in your hometown is from a Mexican sports bar called Carlos’s, but you have to wait a while, because they’re not used to carry-out. So they went there, and did that, and brought back two six-packs. And the three of us sat in Shawn’s room, and we talked about no bullshit, there was no bullshit in that room.

Shawn’s father got sick from Agent Orange, then gave some of that sickness to his son. Now Shawn and his family are homesteaders on land they got for cheap in a hard-times neighborhood. He keeps hearing from vets and conscientious objectors who want another way to heal. Therapy and medicine are only getting them so far and want they need is ritual and restitution. He knows all the names for PTSD, but what he speaks of most is “moral injury.” His remedies are old: work the earth for a year is one, and keep silence. At the end of that year go down into waters then rise up and get dressed in new clothes. So that’s what he’s doing with his life—he’s helping to heal soldiers. And healing is not curing (I can hear you saying this): to be healed is to be made whole.

Liz is like a mother to a whole bunch of girls and like the mother they need now. She knows she’s supposed to be a deacon, even though her church won’t recognize that. But she is one: she washes feet. And Liz keeps helping gay Catholics marry, work that’s also under the radar. She takes the long view, always. She has a massive peace in her, and it spreads. I like it when Liz curates wine, or beer, and she did so that night, and I drank her recommendations, and eased into those hours.

The next day there was more of the same: people who are walking around shining like the sun. A bunch of people who reminded me of you. There were the good men who had become your brothers. There was your nephew and your four lovely nieces. There was your mother and two sisters. We all tried to sing loudly, so that the singing might help them to stand.

After they buried your ashes (a box made by the Trappists in Dubuque, a wild, clear blue sky), we drove back to the church for a lunch. Everyone remembers these marathons of conversation: the man across the table said he’d come to Iowa and you’d block out a weekend so that you two could spend the whole time talking, breaking only for more coffee, liquor, to pee. The woman next to him remembered driving from Colorado to Iowa with you and back. You two stopped talking long enough to sing all of Les Miserables and then you talked the rest of the way.

So many of the people you gathered around you are doing something strange and beautiful. Brenna was there with her husband. At their Worker farm they make, raise or grow almost everything they need. They continue to not pay war taxes, and they live without the internet, and we talked about what it means to be human in an age of machines. The man next to them said he worked in software; now he lives on a farm in New York with a bunch of ex-convicts.

There were neat stacks of your favorite books on the way to the buffet. Parishioners made gallons of the sweet, green smoothies that helped sustain you those last months, and everyone drank some.

Frank compared you to Dorothy Day. Tim said he was honored to be one of your thousand closest friends. Joseph wrote you a poem. He spoke of how you held things in tension: a child’s hope of rescue, and a man’s perfect abandonment.

Your sister spoke of your mother: how she bore everything with you. And that list of everything was fresh and horrifying in our minds: the liver tumor, the tumor at the base of your neck and the tumors down your spine; the pneumonia; the pancreatitis; the cancer in the adrenal glands, lungs, arm, collarbone and spine; the cancer coming out of your bones and eating your bones; the whiplash update from Stage II to Stage IV; when you were swollen and when you were emaciated; when it was hard to walk and eat and move, and impossible to sleep; the confusion, the travel, the hope and dashed hopes. Every pain, every test, every surgery. Every loss and gain and hour. And now the one thing that no mother believes she could bear has come to her. And look, Joshua—somehow she’s bearing that too. So I could hardly breathe when your mother stood and thanked us. She thanked us. Now we have the rest of our little lives to try to be more like her.

I had a ravenous desire to laugh so I stood sometime later and told the only funny story I could muster. It was two days before our wedding and Chini was stranded in Iowa City without a ride; he wanted to get to Colorado, but he didn’t have a car, or a plane ticket, or money for either. Nico and I asked around. The only person who could get him was you, and you didn’t hesitate. You had planned on driving to Los Alamos for a pre-party protest with Sr. Helen Prejean, but instead you turned your car back (you were west of Des Moines) on a peacemaking errand of a different sort. At this point, Chini must’ve been thinking Shit! Shit, shit, shit. What you two had in common was an ex-girlfriend, whom you both missed. He’d had, he said, no intention of getting to know you, and certainly he wasn’t planning to like you. But then a strange thing happened: he did. “Simply put,” he said, “we had a blast.” You drove all that way, listening to music, and talking about life and art and God and war. He was an atheist; you hoped to become a Jesuit. You listened to each other, which is what friends do. You got a military discount and checked in at two a.m. at a hotel somewhere in Nebraska. You drank whiskey at their bar. When you arrived, smiling, as each other’s wedding dates, neither of you was missing your ex-girlfriend.

Jill stood and identified herself as said girl, and spoke of how you two broke up, as even that was peaceable. He brought me a scarf from China, she said. Said he was going to become a priest. We cried. Then we went to a zombie movie.

There were stories and more stories. What everyone was trying to say was We love you. And Thank you. And Thank you for everything.

Now days keep happening, and news.

The quality of bumper stickers is improving. I thought you’d like this one: “Jesus would use a turn signal.” And, “Make awkward sexual advances, not war.”

A satirical newspaper in France decided to publish “crude caricatures” of the Prophet Muhammad in response to the rioting that followed a U.S.-made video called The Innocence of Muslims. A scrap of papyrus from the fourth century appeared; it may or may not be a “new gospel.” A man died for seven days and came back with three lessons. Baxter took Kathleen to a beach in San Diego; he asked her to marry him and she said yes. Your football team is finally winning.

People ask: Does LSD have a bum rap? Is digital self-publishing the end of literature? Will manufacturing jobs return? Can superseeds save us during chronic droughts? Will the legalization of marijuana fund schools? When will the Marshall Islands and the Maldives disappear?

This month is tied for the hottest on record. A new report calls our age “The Age of Western Wildfires.” Another finds that in almost every language the word for red is developed before the word for blue. Millennials don’t buy “enough cars.” I read that, “cities polluted by leaded gasoline turn children violent.” And, “The death of a child increases a mother’s immediate risk of death by 133 percent.” I read that early Christians were called “Christs.”

Early voting is on. The incumbent thinks it’s acceptable to use drones to kill civilians (the Bureau of Investigative Journalism says 176 children have died this way); the challenger characterizes the incumbent as “weak.” He says he needs to “man up” on the “Arab world” and stop “leading from behind.” Both men desire to be the commander-in-chief of a military whose slang for so-called drone kills is “bug splat.” Neither speaks of repealing the “doctrine” of pre-emptive war, and the indefinite detention camp called Guantanamo remains open.

Your mother gave her first interview about the burn pits that you slept by for six months, and manned, unmasked, for weeks. No sane person would ignite any of these things, let alone do so around the clock, for years, in vast amounts: metal, paint, munitions, human waste, hazardous medical material, petroleum products, lithium batteries, computers, guns, tires, vehicles, plastic, hydraulic fluids, unexploded ordnance, and “discarded human body parts.” Soldiers and Afghans at Bagram Airfield called their sickness “Bagram Lung.” An Army captain who was at Abu Ghraib says, “You can’t tell me that was OK…While I was there everyone was hacking up weird shit.” But the VA has only recently acknowledged the “possible side effects,” one of which the EPA identifies as “premature mortality.”

At his school, Nico led a morning assembly about Keats. Keats’s mother abandoned her children, then came home to die of tuberculosis. Keats’s brother died of tuberculosis. Keats nursed them both then died, at 24, of tuberculosis. By way of conversation, I say: “Flannery O’Connor died at 39.” You were only 32.

I keep listening to Alice Coltrane, which is good music for letting go.

In news of a different sort: Several people are running races for you, and you have won a new award.

In my English 1410 class, when we turn to your essay, I fear that I will cry. Students love this essay, even the ones who play Call of Duty all the time. This semester I have a vet who screamed loud and high when I turned out the lights. “Please don’t ever do that,” she said. “Blackout.” Last summer it was a middle-aged father, who left class abruptly in tears. Last year: the girl who told me in the middle of a paper critique that she had been raped by her commanding officer. The year before that: the boy who very much wanted to talk about how he had killed an unarmed, old man under illegal orders; the one who kept failing at his attempts to kill himself; the one who was disturbed by hearing men at bars lie about being Special Forces (he had been Special Forces), because so many women find lethality sexy.

In poetry, we’re on to elegies. The students read, “I am almost afraid to write down / This thing.” (Wright). “It feels like burning / and singing about burning” (Kaminsky), and “A lot of talk’s / plan scarred song.” (Corey). They read, “He was a beautiful man with a slender body that moved with a mixture of grace and sharp geometrical precision” (Kaminsky). “The rivers of his hands / overflowed with good deeds” (Amichai). They read Berrigan: “How strange it is to be gone in a minute!” They read Powell, “who can tell us all about love: a flaying. the sting of a gall upon a hyssop reed”. “Etcetera, etcetera, I try.” (Szybist). “In the morning they were both found dead / … Of the toxins of a whole history” (Boland). “Then the pulse / Then a pause. / Then twilight in a box. […] Then the same war by a different name” (Reddy). They read about “the dreadful martyrdom” (Auden). And how, “All of us wane, knowing things could have been different.” (Gilbert) They read Lease: “Won’t be stronger. Won’t be water. / Won’t be dancing or floating berries. / Won’t be a year. Won’t be a song. / Won’t be taller. Won’t be accounted / a flame.”

They read Celan, who survived his war only to die from it later:

Both doors of the world stand open: opened by you in the twinight. We hear them banging and banging and bear it uncertainly, and bear this Green into your Ever.

Beloved friend, they read Whitman, too: “All goes onward, and outward, nothing collapses / And to die is different from what any one supposed, and luckier.” Then, a week later, they read this from Justice, and I say, Let’s read it aloud; let’s read it slower. “One day the sickness will pass from the earth for good.” Then I say, Thank you. Thank you. And will you please read that again?

I keep reading your e-mails. They’re staggering sometimes. On November 15th, 2009, while caring for your dying father, you wrote:

life enters, arrives from. my father is very near to that place. these months have been the most important of my life. the comings and goings of life are riddled with opportunities to fail to see the eternity in presence. pain, i think, awakens us to that presence—it happens in the fragility of our bodies. there is pain in the beginning of life as in the end. my father has become something quite like ‘more’ present as he begins to depart. he kisses me good morning. and before taking the eucharist. and before i leave and when i come back. and before he goes to sleep each night. the practical matters are of course in excess of what is possible. all of the things to be done, cut, tightened, changed, fixed, sent, washed, copied. and we all do our best. but in the midst of this all, we are being shown how to die. one proof of christian faith of course is death. i have known more of god these months than at any other time.

On February 5th, 2011, while studying at the University of Chicago, you wrote:

everyone after hegel has this untouchable area that they refuse to call god. freud’s unconscious. lacan’s other-than-phallus. heidegger’s other-than-being. derrida’s other-than-otherness. and they all could never have come to be without augustine. i think all of contemporary thinking is a pussyfooting around god. and if whitehead was right, that the history of philosophy is nothing other than footnotes to plato, then i am right, that modernity and its aftermath is nothing but footnotes to augustine. heidegger’s stripping of subjectivity from aquinas (from augustine). derrida’s stripping of subjectivity from heidegger (from aquinas (from augustine)). and there’s this gaping that everyone peers into, if only to manipulate grammar such that verbs cease to need subjects. […] all the while, people continue to come into and pass out of our lives. we eat, we drink, we die.

i’m becoming increasingly obsessed with the ancient conciliar formula of the trinity and the demand the fathers made to understand ‘hypostasis’ as ‘prosopon’ (person) instead of substantia. augustine and aquinas both allowed substantia back into the trinitarian language. since augustine we have been obsessed with the problem of subjectivity and the self. the trinitarian prosopon, however, is irreducibly relational. there is no subject, no substance of self, for person can only be understood in terms of relationship. augustine indeed finds this when he turns into himself and cannot find himself, but that deepest of revelations didn’t hold somehow. terms like ‘father’ and ‘mother’ are incomprehensible without children. or ‘i’ without ‘thou.’ ‘father’ and ‘mother’ do not demarcate substances, they name relations. how much would ethics change if we ditched the notion of substantia from our notion of prosopon? if i am irreducibly relational. if i am ontologically composed of others. every act of violence is suicide.”

That last sentence becomes a chorus in my head. Every act of violence is suicide. Every act of violence is suicide. Every act of violence is suicide. All ethics are relational and there is no such thing as the individual. We are made of each other. Okay.

But my favorite message is one that has no thread, and I can’t remember what preceded it in life. You sent it to me one minute before midnight on January 20th, 2008. The subject line is “happy day.” And the message, in its entirety, is: “happy happy day. j.”

And that should be the final word.

Oh happy, happy day.